According to the World Health Organisation, cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for nearly 10 million deaths in 2020. The most common cancer cases were breast, lung, colon and rectum, and prostate cancers. Many individuals diagnosed with cancer have a high chance of being cured if diagnosed early and treated effectively. Thanks to the advances in early detection and treatments, survival rates are getting higher, and people are now living longer. However, cancer treatment centres often solely focus on monitoring and treating physical health symptoms. The fact that the mental health needs of people often receive little attention presents a significant global challenge.

People who received a cancer diagnosis are at heightened risk of developing anxiety, mood, and substance abuse disorders, which can adversely affect their survival and quality of life (Zhu, Fang, Sjölander, Fall, Adami, & Valdimarsdóttir, 1964-9). Depression and anxiety are the most commonly diagnosed psychological disorders in cancer survivors (Mitchell, Ferguson, Gill, Paul, & Symonds, 2013). In recent years, addressing depression and anxiety among individuals living with and beyond cancer has become a priority in both clinical practice and research (Niedzwiedz, Knifton, Robb, et al., 2019).

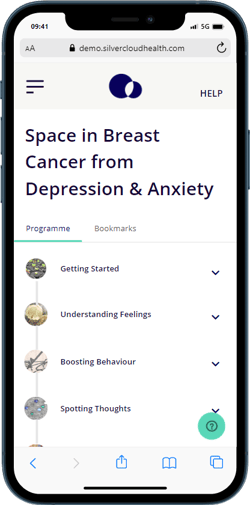

In a previous blog, we described how and why we developed an internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy programme to address depression and anxiety symptoms in breast cancer survivors who completed their active cancer treatment. Our programme aims to help individuals learn and practice strategies and techniques to actively counteract cancer-related distress. Depression & Anxiety Programme for Breast Cancer consists of 7 modules and the module content is presented below.

Myths for Survivors after Cancer Treatment

One of the challenges of the period after treatment completion is related to unrealistic expectations , which can hinder survivors’ positive psychological adjustment (Stanton et al., 2005). These expectations can also be described as the myths of treatment completion. There are four common myths:

Myth 1: The end of treatment should be celebrated

Although survivors often experience relief and positive emotions after treatment completion, many also discover that they are only beginning to process what happened, as survivors often do not have a chance to process their emotions during the treatment. Therefore, the treatment completion may bring feelings of loss rather than happiness and celebration.

Myth 2: The person should recover soon after medical treatment is over

Recovery may not happen soon after completing treatment as it requires time, effort in processing feelings, and support from significant others. Some survivors may continue experiencing fatigue, concentration, and memory problems beyond treatment completion despite all these. If individuals are pressured to recover soon, they may push themselves to overcome their own physical limits too quickly, resulting in frustration.

Myth 3: The person should return quickly to their pre-diagnosis sense of self

Cancer diagnosis and treatment are challenging experiences, and one can’t expect survivors to act as though nothing has happened. A new altered self and new meanings in life are possible for survivors. Individuals may experience a new sense of vulnerability with the physical reminders of the cancer treatment. However, they may also experience a new sense of personal strength, life appreciation, and enhanced relationships.

Myth 4: The person should no longer need support once the treatment ends

Cancer survivors often find that the net of safety and support during the acute diagnostic and treatment period diminishes after treatment completion. However, many survivors need emotional support during the adjustment period and a safe environment to express their feelings and concerns. Loss of social support at this period can contribute to a sense of isolation and increased psychological distress.

Depression and Anxiety in Cancer Survivors

Research shows that 17.9% of long-term cancer survivors continue to experience anxiety, and 11.6% of survivors experience depression (Mitchell, Ferguson, Gill, Paul, & Symonds, 2013). Depression and anxiety in cancer survivors are associated with significant impairments. Untreated depression and anxiety can hinder recovery and decrease quality of life and survival time (Niedzwiedz, Knifton, Robb, Katikireddi, & Smith, 2019). For example, women with breast cancer and comorbid depression have a higher prevalence of metastasis and experience more intense pain and fatigue than those without depression (Chida, Hamer, Wardle, & Steptoe, 2008).

Many interacting factors influence the development of depression and anxiety among cancer survivors. These factors consist of:

- individual characteristics (e.g., age, gender, ethnicity, genetics, marital and cohabitation status),

- social and contextual factors (e.g., education level, employment status, household income, social support, healthcare system),

- prior psychological factors (e.g., pre-existing psychiatric disorders, personality),

- psychological response to diagnosis (e.g., distress, coping behaviour, denial, anger, fear, grief, resilience),

- characteristics of cancer (e.g., diagnosis experience, symptoms, cancer type, stage, prognosis and curability, recurrence),

- cancer treatment (e.g., treatment modality and dose, side effects, long-term complications, cost of treatment, response to treatment).

Online CBT for Depression and Anxiety in Cancer Survivors

Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for intense pain and fatigue has proven effective in treating depression and anxiety among cancer survivors (Ye et al., 2018). However, many cancer survivors cannot access psychological therapies and remain untreated due to the under-recognition of their psychosocial needs and the lack of available mental health clinicians (Fallowfield, Ratcliffe, Jenkins, & Saul, 2001). In a previous blog post, we discussed the barriers for people living with long-term health conditions to access psychological therapies. Online CBT programmes have been developed to overcome these barriers to accessing evidence-based psychological therapies such as CBT.

These programmes involve the same content and principles of CBT (psychoeducation, cognitive and behavioural techniques) used in face-to-face therapy but are usually delivered using structured modules written in text.

The acceptability and effectiveness of online CBT programmes are well documented in treating depression and anxiety in the general population (Carlbring, Andersson, Cuijpers, Riper, & Hedman-Lagerlöf, 2018; Etzelmueller, Radkovsky, Hannig, Berking, & Ebert, 2018). Similarly, online CBT was found effective for depression and anxiety among individuals with chronic health conditions (Mehta, Peynenburg, & Hadjistavropoulos, 2019). Studies with cancer survivors are recently emerging, with promising findings showing large reductions in their depression and anxiety symptoms (Alberts, Hadjistavropoulos, Dear, & Titov, 2017; Murphy et al., 2019).

One may ask, what are the advantages of online CBT programmes for cancer survivors? Privacy of the online programmes, as opposed to face-to-face therapy, is one thing that makes them more appealing for individuals who are more reserved, private, and concerned about stigma (Alberts, Hadjistavropoulos, Titov, & Dear, 2018; Karageorge et al., 2017). Many survivors who used an online CBT programme also liked its flexibility, and convenience and thought it helped them feel less alone following cancer treatment. Indeed, these advantages are not unique to programmes for cancer survivors, and they apply to all online CBT programmes for chronic illnesses.

Scientific evaluation of our Breast Cancer programme

In our recent publication in a peer-reviewed journal, we describe the details of the scientific evaluation of the Depression & Anxiety Programme for Breast Cancer programme. In this study, we conducted a randomised controlled trial with 72 breast cancer survivors to investigate whether an online CBT programme specifically tailored for breast cancer survivors is effective in reducing their depression and anxiety symptoms. We compared the breast cancer programme recipients against a treatment-as-usual control group on depression and anxiety at post-intervention and 2-month follow-up. Intervention participants received weekly asynchronous guidance and post‐session feedback from non-clinician supporters over 8 weeks. The treatment-as-usual group continued their usual care recommended by their healthcare team. The programme’s effects were also evaluated on secondary outcome measures of quality of life, fear of cancer recurrence, active and avoidant coping and perceived social support.

Our results showed that survivors who received the online CBT intervention had significantly lower depression and anxiety scores 2-months after the intervention had ended. The engagement with the programme was high, survivors logged in approximately 16 times and spent 4 hours and 20 minutes in the programme. Intervention participants also had a trend indicating improvements in their quality of life and decreases in the use of avoidant coping from pre-intervention to 2-months after the intervention completion. It is important to highlight that these results were achieved with weekly non-clinician post-session feedback.

The positive findings suggest that online CBT programmes can be an effective and accessible alternative to address the mental health needs of an increasing number of cancer survivors. Customizing interventions for cancer survivors and those living beyond can enhance mental health support accessibility and meet the needs of most individuals at reduced costs. The integration of these interventions in primary health care can help reserve resource-intensive interventions for those most in need and prevent longer-term depression and anxiety and its negative impact among cancer survivors.

Conclusion

Online CBT programmes have a considerable potential to facilitate psychological recovery and alleviate depression and anxiety symptoms among cancer survivors who completed their treatment. Considering the detrimental consequences of depression and anxiety for cancer survivors and the lack of integrated service provision following medical treatment, research in this area should be prioritised. SilverCloud is committed to developing evidence-based programmes to help empower individuals living with chronic health conditions to manage their psychological well-being. We believe that providing mental health support to individuals during the recovery process is critically important. Hopefully, more and more cancer survivors will have access to effective and accessible mental health support.

References

- Akkol‐Solakoglu S, Hevey D. Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and anxiety in breast cancer survivors: results from a randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2023;1‐11. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.6097

- Akkol-Solakoglu, S., Hevey, D., & Richards, D. (2021). A randomised controlled trial of an adapted internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (iCBT) with main carer access for depression and anxiety among breast cancer survivors: study protocol. Internet Interventions. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2021.100367

- Alberts, N. M., Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Dear, B. F., & Titov, N. (2017). Internet-delivered cognitive-behaviour therapy for recent cancer survivors: a feasibility trial. Psycho-Oncology, 26(1), 137–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4032

- Alberts, N. M., Hadjistavropoulos, H. D., Titov, N., & Dear, B. F. (2018). Patient and provider perceptions of Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for recent cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 26(2), 597–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3872-8

- Carlbring, P., Andersson, G., Cuijpers, P., Riper, H., & Hedman-Lagerlöf, E. (2018). Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 47(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2017.1401115

- Chida, Y., Hamer, M., Wardle, J., & Steptoe, A. (2008). Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nature Clinical Practice Oncology. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncponc1134

- Etzelmueller, A., Radkovsky, A., Hannig, W., Berking, M., & Ebert, D. D. (2018). Patient’s experience with blended video- and internet based cognitive behavioural therapy service in routine care. Internet Interventions, 12(August 2017), 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2018.01.003

- Fallowfield, L., Ratcliffe, D., Jenkins, V., & Saul, J. (2001). Psychiatric morbidity and its recognition by doctors in patients with cancer. British Journal of Cancer, 84(8), 1011–1015. https://doi.org/10.1054/bjoc.2001.1724

- Karageorge, A., Murphy, M. J., Newby, J. M., Kirsten, L., Andrews, G., Allison, K., … Butow, P. (2017). Acceptability of an internet cognitive behavioural therapy program for people with early-stage cancer and cancer survivors with depression and/or anxiety: thematic findings from focus groups. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25(7), 2129–2136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3617-8

- Mehta, S., Peynenburg, V. A., & Hadjistavropoulos, H. D. (2019). Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic health conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 42(2), 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-018-9984-x

- Mitchell, A. J., Ferguson, D. W., Gill, J., Paul, J., & Symonds, P. (2013). Depression and anxiety in long-term cancer survivors compared with spouses and healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Oncology, 14(8), 721–732. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70244-4

- Murphy, M. J., Newby, J. M., Butow, P., Loughnan, S. A., Joubert, A. E., Kirsten, L., … Andrews, G. (2019). Randomised controlled trial of internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for clinical depression and/or anxiety in cancer survivors (iCanADAPT Early). Psycho-Oncology, 29(1), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5267

- Niedzwiedz, C. L., Knifton, L., Robb, K. A., Katikireddi, S. V., & Smith, D. J. (2019). Depression and anxiety among people living with and beyond cancer: A growing clinical and research priority. BMC Cancer, 19(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-019-6181-4

- Stanton, A. L., Ganz, P. A., Rowland, J. H., Meyerowitz, B. E., Krupnick, J. L., & Sears, S. R. (2005). Promoting adjustment after treatment for cancer. Cancer, 104(11 SUPPL.), 2608–2613. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21246

- Ye, M., Du, K., Zhou, J., Zhou, Q., Shou, M., Hu, B., … Liu, Z. (2018). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy on quality of life and psychological health of breast cancer survivors and patients. Psycho-Oncology, (September 2017), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4687

- Zhu J, Fang F, Sjölander A, Fall K, Adami HO, Valdimarsdóttir U. First-onset mental disorders after cancer diagnosis and cancer-specific mortality: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(8):1964–9.